An African Scops Owl comes to visit our campsite

by Anthony Stidolph

I am, by nature, a wanderer. For me there is nothing quite like the thrill of departure, the joy of being on the road again, of heading off to remote and cut-off places.

As an antidote to this restlessness I have travelled the length and breadth of South Africa searching out new places I can claim as my own. In recent years this has involved launching several expeditions up to the Limpopo, along the way taking in Punda Maria and Pafuri in North Kruger, Mapungubwe, Ratho on the Botswana border, Hans Merensky on the Groot Letaba, the forests of Magoebaskloof, parts of the Soutspanberg and that little-known gem, Blouberg Nature Reserve near Vivo.

Having explored and fallen in love with this sun-drenched landscape, my birding partner Ken and I recently took a notion to recreate these epic treks by heading back up there once again, only, this time, adding Marakele National Park, which would be new country for me.

A Tshwana word, aptly meaning “Place of Sanctuary”, Marakele falls within a transitional zone between the dry western habitat, made up mostly of Kalahari thornveld, and the typical bushveld country of the moister eastern sections of South Africa. It also lies within the Waterberg range of mountains, with an altitude ranging from 1050 metres on the plains to 2088 metres at its highest point.

Because of this broad range of vegetation types and its diverse topography the area boasts a wide variety of game (including the Big Five and Wild Dog) and an abundant bird life. Its biggest attraction, for birders anyway, is the around 800 breeding pairs of Cape Vulture which nest high up in the cliffs of the Kransberg

Arriving at the park, which is situated about twenty kilometres north of the old iron-ore mining town of Thabazimbi, we set up camp and then headed off on our first drive. I was immediately rewarded with my first lifer of the trip – a Greyheaded Kingfisher.

As we sat having a celebratory beer that night, listening to the clear, articulated noises of the bushveld at night, a tiny African Scops Owl landed on a branch above us and began its odd but strangely comforting, frog-like, “Prrrt…prrrt…prrrt…” call. This was more like it. My latest Excursion Into The Great Unknown had officially begun.

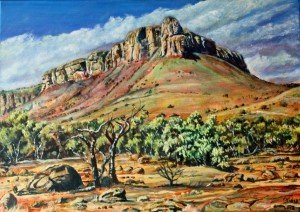

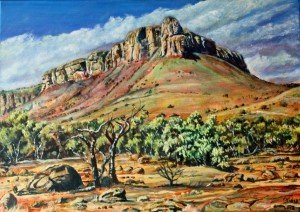

Anthony Stidolph’s painting of The Kransberg in Marakele National Park. For Sale – contact Stidy at stidy@sai.co.za (42×60)

The next day we were up at dawn and driving through heavy bush country towards the impressive pass that leads up to the top of the Kransberg mountain. A friend of ours had told us that her biggest concern going up this narrow, winding, precipitous road, was what she would do if she encountered another vehicle coming down the other way as there is little room to pass. That proved to be the least of our worries.

Rounding one steep-sided corner we suddenly found ourselves coming face-to-face with a young elephant bull that had stepped out on to the road. Having been in this situation many times before, Ken immediately pulled up short, stopping a sufficient distance from the animal so as not to make it feel threatened or think that we were encroaching on its space. It didn’t help.

Coming face-to-face with a wild animal so much bigger than yourself can be a slightly intimidating experience and this one decided to remind us of its size advantage. Without even affording us the courtesy of a warning mock charge, it let out an almighty bellow and came thundering down the road.

There was nothing to do but slam the car into reverse and head back down the road with me craning my head out of my window, shouting directions, while Ken did the same on his side.

The kilometre or so we drove in this manner was like a rapid ride through eternity. We kept hoping that each time we rounded a corner and the elephant lost sight of us it would lose interest. No such luck. The beast definitely did not like the cut of Ken’s jib and was determined to drive us clear off his mountain stronghold.

We went back down into the valley and somehow – and I shall never know how we did it – managed to do so without plunging down the mountain side or getting stomped on by the elephant. Once safely back on the flat we found a turning point, backed into it and sped off in the direction we had earlier come from.

A half-an-hour or so later we gingerly ventured back but, very bravely, decided to allow another vehicle – that had come driving up while we were parked on the side of the road observing, of all things, a Neddicky (the ultimate Little Brown Job), while considering the sagacity of continuing on our journey – go up ahead of us. Once we had seen they had safely cleared the ridge we sailed forth ourselves, this time, thankfully, unmolested.

At the top of this particular stretch the road evens out on to a trough through which you drive before getting to tackle the final, most spectacular, stage of the mountain. Here the road begins an even more torturous ascent. On the one side rise the naked sandstone towers of the Kransberg massif itself, weathered into the shapes of fantastical beasts and strange deformed reptiles. On the other side the slopes plunge steeply down into a treeless, meadowy grassland in which several more elephant and a herd of wildebeest were feeding.

As we advanced the road got narrower and narrower. What got us perspiring heavily all over again was that there were yet more fresh elephant droppings at regular intervals all along its surface, virtually to the top.

On the summit it was like another world. The view was colossal. Below us the mountain stretched away in every direction before dropping down, in a series of steps, to the plains, fading away into the blue distance.

Immediately in front was another castle-like knob, a labyrinth chaos of rock, fitted with clefts and chimneys. It was here the vultures nested. There were many of these large, endangered raptors wheeling gracefully above us, trailing their shadows on the ground beneath them.

The protea-covered hillsides on top of the mountain also provide a home for some other unusual species like the Gurney’s Sugarbird and the Buff-streaked Chat, birds which I more commonly associate with the Natal Midlands, where I live, and the foothills of the Drakensberg. Another occupant is the Kransberg Widow, a very rare and beautiful butterfly which puts in an appearance in November and early December and then, like Cinderella, sheds its finery and disappears. This is the only place in the world where it occurs.

We were reading all about the insect on a large information board they have erected up there, alerting us to its presence, when one came fluttering past. A few minutes later it came fluttering back again … and again. It may be scarce but it certainly wasn’t shy about showing off its beautiful cream markings.

A cold wind was blowing across the mountain top and a storm was brewing in the distance and so, after a warming cup of coffee, which we shared with a pair of very tame Cape Buntings and a cheery Mocking Cliff-Chat, we made our way back down the same twisting road, this time without having to face down any elephants with murder on their minds. Heading into camp I did, however, have another good sighting of two more Greyheaded Kingfishers, dive-bombing a family of Banded Mongoose.

Two days later, in Blouberg, I had an even better view of the kingfisher sitting at the end of a dead branch. This meant that after fruitlessly searching for the elusive bird for years I had now seen four in four days …

The grumpy pachyderm who had chased us down the Kransberg may have scared me witless, but I couldn’t help wondering afterwards if he hadn’t deliberately engineered the whole encounter just to make sure I kept running into the bird!

ANTHONY STIDOLPH

Where is Marakele National Park?