THE TROUBLE WITH ELEPHANTS 0

by Anthony Stidolph

I am not a man who deliberately courts disaster or intentionally goes looking for bad experiences. By the same token, I am not such a fool as to think the odd mishap won’t occasionally befall me. And when you go travelling with my birding partner Ken, rotten luck does have a habit of following you around.

For example: on a recent trip to Marakele National Park we found ourselves being chased down a narrow, twisting mountain pass in reverse by a very angry elephant who clearly resented our presence in his private domain. Luckily – I have a feeling some benevolent deity saw fit to intervene – we survived that harrowing encounter. What I did not realise was that more trouble with elephants lay ahead…

From Marakele we had followed a circuitous route that took us to Blouberg Nature Reserve and then cut east along the base of the Soutpansberg range to Punda Maria in North Kruger. We planned to camp the night here and then press on to Pafuri the next day, where we hoped to get in some good birding.

Up until now the weather had been kindly – more spring than summer and I had even found myself wearing a jacket in the evenings and early mornings. In Kruger, however, the hot weather we had been expecting all along finally caught up with us, with the temperature soaring up to 39 degrees. The air around us was heavy and listless and steamy, almost tropical, perhaps hardly surprising since we had crossed over the Tropic of Capricorn some days before.

Eager to be off, I was up early the next day although I had to first wait for Ken to complete his complicated early-morning-ablution rituals. Once he was done with that, we set off northwards through the familiar vastness of flat grassland and mopane trees. On the way we stopped to allow the biggest herd of elephants I have ever seen cross the road. Shortly afterwards we were forced to repeat this exercise for an even bigger herd of buffalo.

The common bird in this neck of the woods – or at least the most vocal – is the Rattling Cisticola. There seemed to be one trilling its silly head off on top of virtually every second tree we passed.

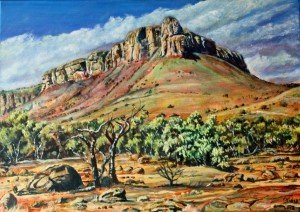

As you draw close to Pafuri, the terrain starts to break up and rearrange itself and you are suddenly confronted by the arresting sight of Baobab Hill, with its commanding views over the Limpopo Valley. In the early days this iconic hill served as both a landmark and sleepover point for the ox-wagons travelling up from Mozambique.

By the time we got to Pafuri the sun was high and blazing. There had obviously been no rain here this season and the grass was pale and dry, although the trees had mostly come out in leaf.

At the crossroads we turned left down the Nyala Drive, which takes you into some wonderfully hilly country before taking a lazy loop back to the main road. Ken likes this less-used drive because, he says, it often throws up unexpected surprises.

There wasn’t much on offing this time around besides the usual suspects – Meves’s Starlings, Arrowmarked Babblers, Whitefronted Bee-eaters and Emeraldspotted Wood Dove. We passed a solitary elephant but he paid us no mind.

On the top of the small, baobab-clad hillock, directly above where the road swings back, is the Thulamela archaeological site, a restored Zimbabwe-type ruin. Unfortunately you can only go up with a guide and because of our tight schedule we did not have time for that.

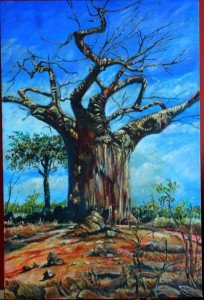

One of the commanding Baobab trees of northern Kruger.

This painting by Stidy is available for sale. 42×60 stidy@sai.co.za

From the Nyala Drive we crossed back over the main tar road and followed the dirt track that takes you to Crooks Corner, where the brown waters of the Luvuvhu collide with the blue of the Limpopo. The combination of water, sun and rich alluvial soils has led to a proliferation of vegetation along the rivers’ banks so that you drive through a glittering tunnel of Sycamore Figs, Nyala trees, Jackal Berry, Ana and Fever trees.

Crooks’ Corner, where you can get out of your cars, marks the border between South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. In the early 1900s this remotest of places gained its moniker and dodgy reputation with gun-runners, fugitives and others on the run from the law, using it as a safe haven because it was easy to hop across the border whenever the police from one country approached.

Distinctly, there was a sense of a frontier on that lazy meandering river, although I don’t think the solitary Saddlebilled Stork fishing in its waters gave a fig where the international boundary lay or as to who held sovereignty over the country he was standing in.

Normally, it feels like you can’t get much further away from civilization than here, but we had chosen a busy weekend to visit so it was like a major thoroughfare with a steady stream of traffic passing through. Many of the visitors didn’t even bother to wind down their windows or get out of their luxury 4x4s because it would mean switching off their air-conditioners. They just drove in, stopped, glanced around and drove out again, leaving me to wonder why they had bothered to come all this way …

Needless to say Ken – who, contrarily, makes it a rule to ALWAYS switch off his air-conditioner when he enters a park because he likes to experience Africa in all its extremes – and I did get out.

Rich plant life invariably means rich animal and bird life and Pafuri is no exception. In the past the storied riverine forest has provided both of us with some good sightings. It was here I saw my first Gorgeous Bush Shrike, Bohm’s Spinetail and Ayre’s Hawk Eagle. I have also recorded Lesser Jacana, Greencapped Eremomela, Hooded Vulture, Tropical Boubou and the palm-dwelling Lemonbreasted Canary.

This time, we could hear both the Gorgeous Bush Shrike and a melodious Whitebrowed Robin-Chat calling from the depth of a nearby thicket but could not entice either of them out. Instead we had to make do with a bunch of waders and a noisy party of Trumpeter Hornbills who, I think, were off to join the celebrations in neighbouring Zimbabwe.

It was now well past lunchtime so we doubled back to the Pafuri picnic site on the edge of the Luvuvhu. Feeling somewhat dehydrated, I was desperate for an ice-cold coke but had to wait patiently in queue behind an American who was explaining to the bemused coke seller-cum bird guide – who, I suspect, knew the answer but was too polite to say so – what a turkey is (“It’s a big black bird with a red head”).

At this juncture of its journey the Luvuvhu is always a ruddy brown colour such as might be achieved by mixing cans of tomato soup with cans of chicken soup. There was an enormous crocodile lying directly opposite us, not, as one would expect, by the water’s edge but high up on the bank under some trees. I had a feeling some unsuspecting animal was in for a nasty surprise.

On the way back to Punda Maria, we took the shortcut via Klopperfontein Dam, another place which can throw up some unexpected treats even though the area around the dam has been grazed as smooth as a billiard board. Sure enough, we were rewarded with a wonderful sighting of a Painted Snipe snooping around in the shallows of the nearby stream.

It was getting on for late afternoon by now. Ken consulted Emily, his prissy, admonishing Satnav, and worked out how far we had to go and what time we had to do it in. What neither factored into their calculations was our old nemesis, the elephant.

The first one, which we encountered just after Klopperfontein, kept us waiting for ages, while it feasted on the side of the road, before moving off into the surrounding bush. A little later we passed him siphoning water by the trunk load out of the top of a reservoir.

We ran in to the second one on the home stretch with the hills around Punda Maria in plain sight. Although this bull appeared much more amiable then the one who had chased us down the mountain in Marakele, he had obviously decided he held all the rights to this road.

The whole thing quickly degenerated into a stage farce. We kept reversing and reversing and he kept trundling on towards us. I suspect he was headed for his evening sundowner at the same reservoir where the other elephant was sloshing water around.

One of us had to blink and we did so first. Muttering angrily to ourselves about the beast’s poor road etiquette, we turned around and headed back to the tar and took the much longer route home to Punda Maria.

In Kruger, as in other parks, you are not supposed to arrive in camp after dark, which we now did, finding the gate locked on us. Fortunately, the guard was still at his post but Ken had to use all his silky skills as a sports writer and commentator to try to convince him it wasn’t really our fault. I am not sure he bought our explanation, but he let us through without imposing a fine.

So we drove into camp feeling like a pair of naughty schoolboys who had just been caught bunking …

But we were not done yet. We arrived to a scene of utter devastation – in our absence a troop of baboons had ransacked the place, flattening my tent, breaking its poles and ripping gaping holes in the fly-sheet (even though there was nothing inside but my bedding and clothes), as well as scattering our possessions far and wide.

To tell you the truth I was getting seriously tired of this. I had just bought the tent to replace the one that got ripped by monkeys in Mapungubwe on my last trip which, in turn, I had bought to replace the one that had suffered a similar fate at the hands of baboons when I attended a wedding in De Hoop Nature Reserve in the Western Cape. At the rate I was getting through tents, it would have been cheaper to have just booked into a luxury lodge!

I am not sure what one does about this menace. The problem is both monkeys and baboons have become habituated to both human beings and human beings’ food.

We did discover afterwards that there was supposed to be a guard on duty to stop these opportunistic raids but, even though the campsite was virtually booked out, he had decided to take the Sunday off …

I was still sulking about my poor tent the next morning when we drove out of the gate, destination Mapungubwe. There to wish us on our way was the scruffiest Ground Hornbill I have ever seen. It flew up into a tree from where it regarded us quizzically through its girlishly-long eyelashes.

For some reason the sight of that lugubrious bird, peering around its branch, cheered me up no end. It made me realise that on the Richter Scale of Travel Disasters we had got off relatively lightly compared to what other great explorers, like David Livingstone or Scott’s Antarctic expedition, had been forced to endure…

ANTHONY STIDOLPH

![IMG_2733[1]](http://kenborland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IMG_27331-300x200.jpg)

![IMG_2734[1]](http://kenborland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IMG_27341-e1532094509404-300x181.jpg)